Portola RECON member Warren asked for more details about how I go from images to orbits for the TNOs we’re interested in. Let me explain.

Most people know that planets, asteroids, and TNOs all orbit the Sun. The force of gravity keeps everything bound together into what we know as the solar system Remember about Kepler and Newton? From their work we have a mathematical theory that describes motion under the force of gravity. If you have just two objects, like the Sun and a single TNO, this simple theory can perfectly describe the motion of these two, forever. The path the TNO takes through space is called its orbit. Now, in our case, we really care more about the mathematical description of its motion. Kepler’s mathematical formalism requires the determination of six parameters at some specific time. Those parameters collectively are known as orbital elements and consist of the semi-major axis, eccentricity, inclination, longitude of the ascending node, longitude of perihelion, and the mean anomaly. From these values it is possible to calculate where an object is at any time.

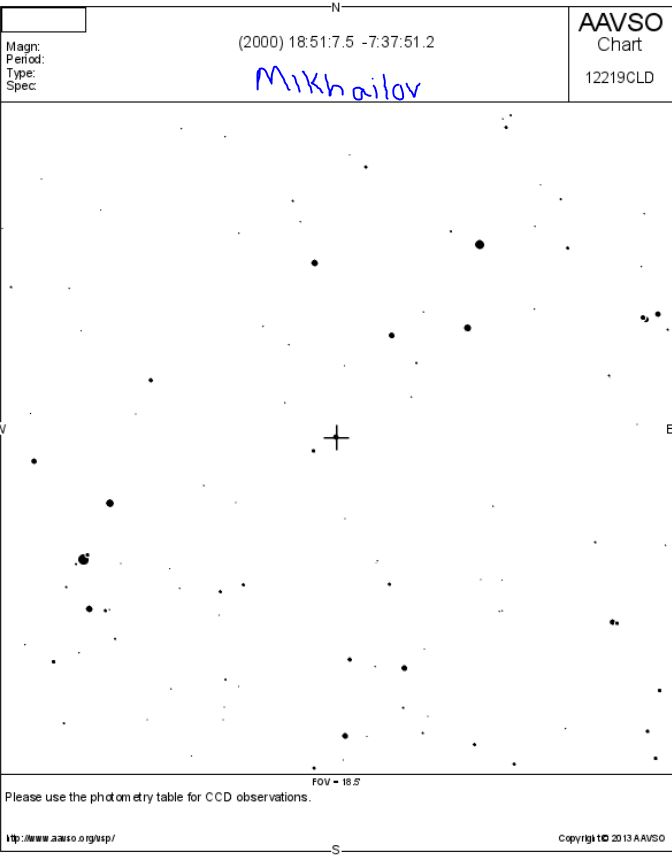

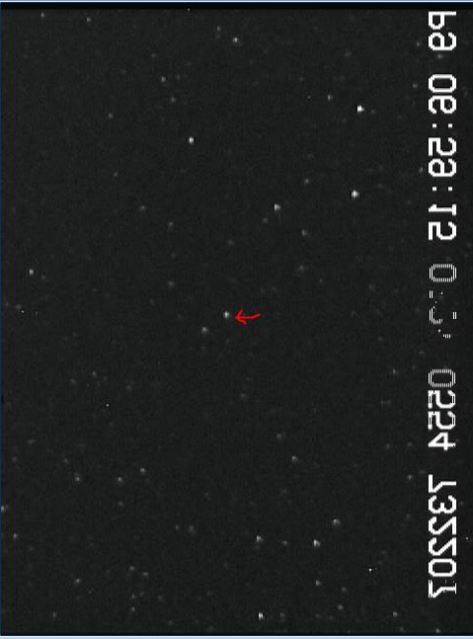

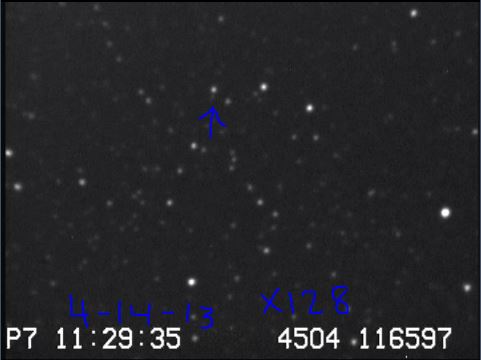

Ok, so that’s the perfect setup. What’s it like in real life? First of all, you can’t just divine or even directly measure any of the orbital elements. Second, there are far more than two objects in our solar system. Here’s where it starts to get tricky (and sometimes interesting, but that’s a story for another day). Let’s just worry about the first part for now. What can we measure? Well, our most useful instrument is a camera. With this we get an image of the sky that contains stars, galaxies, and perhaps our TNO at some known time and from some known location. Most, if not all, of the stars and galaxies will be objects whose positions are already known. These are known as catalog objects and are used as positional references. Using the catalog objects we can calibrate the correspondence between a position in the image to the coordinates on the sky (known as the celestial sphere). Most of the time this is rather simple. You work out the angular scale of the

image (arc-seconds per pixel) and the sky coordinate of the center of the image. From that you can then calculate the sky coordinate of any pixel. When you work with wide-field cameras there are often distortions in the image that need to be mapped out. Ok, so you see you TNO on the image and then compute its position. This position, known as right ascension and declination, is a pair of angles measured from a single reference point on the sky.

Having a single position is not good enough yet to compute an orbit. Not only do you need to know where it is but you also need to know its velocity (speed and direction). With perfect data, you could simply wait some time from your first picture and then take another. These two positions now give you a measure of the velocity. There’s a

catch, though. First, you never have perfect data. That means your limited in what you can learn in just two measurements. There’s something you cannot easily measure from just two positions. On the sky you get a good measurement of the sky position and the velocity as seen in the sky. You do not have good information on how far away it is or how fast it

is moving toward or away from you. A clever guy named Vaisala figured out a trick for working with limited data like this. His trick was to guess what distance the object is at and you guess that it’s currently at perihelion. Perihelion is when the object is at its closest distance from the sun during its orbit. Unfortunately, with just two points there are lots of guesses that will give you a reasonable orbit but you don’t yet know which is right. Still, it can help you to pick something reasonable that can be used to predict where it will be the next few nights.

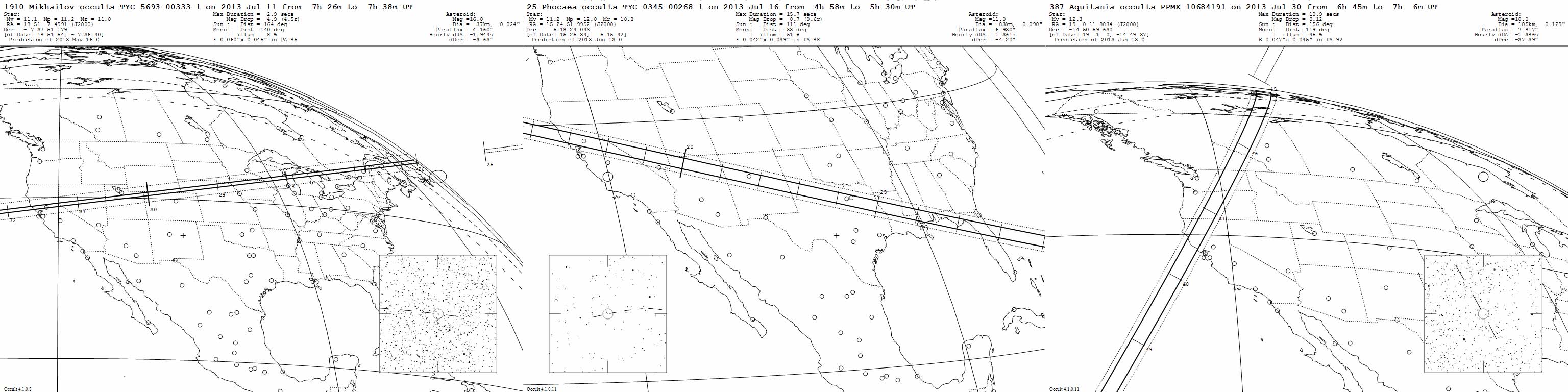

As you continue to make measurements (more images at later times), you build up what is called the “observational arc”. Formally, this is the time between your first measurement and your last measurement. As this time gets longer, you can get better and better quality orbits. By that I mean the orbit you think you have gets closer and closer to the true orbit. Now, what about that second thing I mentioned before? Right, there are other things around than just the sun and the one TNO. That means the position and velocity of everything in the solar system depends slightly on the position of all the other objects in the solar system. To get a perfect description you really need to have a catalog that is 100% accurate and complete. This isn’t very likely so we’re resigned to always having orbits that are really just approximations. Are these good enough? In most cases, all you want to do is to find a TNO in your telescope again. That’s the easiest condition to meet. If you want to see an occultation of a star by a TNO we need a very precise orbit. Finally, if you want to send a spacecraft to a TNO we need something extremely good.

You can make your orbits better in different ways. The easiest is to simply wait and then take another picture. Bit by bit as time marches on you will get a better and better orbit. How long you have to wait for a good orbit depends on where the object is in the solar system. Objects closer to the Sun move faster and in so doing let you get a good orbit more quickly than a slow moving object. For a main-belt asteroid orbiting between Mars and Jupiter you generally get an excellent orbit (good for occultations) in just 4-5 years. Note that the one thing that does you no real good is to just take lots and lots of pictures. Time is a lot more valuable than the number of measurements. In fact, on a single night you get the same information from 2-4 observations as you would from a thousand in one night. In the early days after discovery you need to observe more often but then things spread out considerably. One rule of thumb I use is the “rule of doubling”. This rule says that you want to wait twice as long as your current observational arc before you both to measure it again. Here’s an example: you find a new TNO on some night with two images that are one hour apart. The third image should be three hours after the first image. The fourth should be at 6 hours, the fifth at 12, then at 1 day, 2 day, 4 day, 8 day, 16 day, 32 day, and so on. After a while you are waiting years or even decades for that factor of two. Now, this really isn’t a rigorous rule, after all, the Sun keeps coming up making it hard to see your object. Still, if you followed this rule you would never lose a newly discovered object.

Another way to get better orbits if you are impatient is to use a more accurate catalog. The quality of your positions for your TNO is only as good as your catalog. If you use a better catalog you get better positions. The problem is that this is really hard to do. We’ve got really good catalogs now but they could be a lot better. In fact, there is a European mission, named Gaia and planned for launch later this year, that will measure all the star positions to an unprecedented accuracy. I can’t say enough about this mission. It will completely revolutionize occultation observations by making it very easy to predict where the asteroid shadows will fall. Alas, it’s going to be quite a few years before these results are available and work their way into better TNO positions.

A third way that works really well is to use radar. The Arecibo and Goldstone radio telescopes are used for this with near-Earth asteroids where they bounce a signal off the asteroid and analyze the return signal. Radar is especially valuable because it can directly measure distance to the target and how fast it is moving toward or away from us. The problem is that the objects have be close. It’s just not practical to use this method on a TNO.

Now, think about sitting at the telescope and trying to get better orbits. That’s what I was doing in March, 2013. I have information on every measurement ever made of a TNO (asteroids too, for that matter) and I know something about how good the orbit is. I’m looking for objects whose positions are poorly predicted that have not been seen in a while. This is a very complicated thing to do at the telescope and I have some very powerful software that helps me keep track of what I’ve done and what I might be able to do as the night goes on. I can say that 3 clear nights on a big telescope can be a very exhausting experience but well worth the effort. Then, once the night is over there is the task of getting the positional measurements off the images. I’ll leave that discussion for another time.